Through military nursing, a group of more than 500 New Zealand women participated directly in the Great War, including Lottie (Charlotte) Le Gallais, who is our seventh larger-than-life figure in Gallipoli: The scale of our war (above). This blog is about her war and the impact it had on the Le Gallais family.

Lottie was on the nursing staff (above) of Auckland Public Hospital when war broke out, and was one of 79 in the second contingent of New Zealand nurses chosen, in June 1915, to serve overseas. From this group of 79, Lottie was selected to work on the hospital ship Maheno, which would transport sick and wounded soldiers to hospitals away from Anzac Cove.

Heading to war

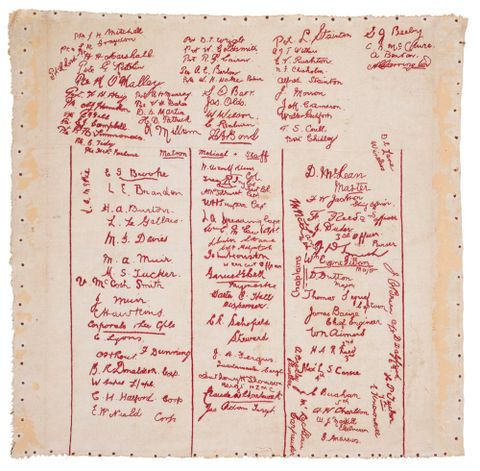

The Maheno left Wellington on 11 July 1915 (above). Many on board the Maheno signed this linen cloth (below) during the voyage. The nurses embroidered the names in red, and the cloth was sent back home to be sold to raise funds for the war effort.

When the Maheno arrived in Egypt in August, Lottie contacted her sweetheart, Charles ‘Sonnie’ Gardner and described the effects of the fighting on Gallipoli:

‘It was terrible to see the wounded, they all say Gallipoli is hell and death…from what we can hear, the losses are awful’ (23 August 1915).

For three months, Lottie endured ‘terrible clean ups’ on the Maheno as the ship shuttled sick and wounded men between Gallipoli and hospitals on Lemnos island and in Egypt, Malta, and England.

Two brothers and a sister

Like many others, more than one member from Lottie’s family volunteered for military service. Lottie’s brother Leddie departed in April 1915, and Owen left later that year. The third Le Gallais brother, Kenneth, was keen to join up, but Owen discouraged him.

Before landing on Gallipoli in June, Leddie’s troopship anchored off the island of Lemnos, where he composed a final letter to his family:

‘Well, Dad’, he wrote. ‘I never thought that I would be a soldier, but now I am one, I am determined to be a good one … If I have bad luck , well I suppose it had to be’ (3 June 1915).

Leddie was killed in action on 23 July 1915 – a month before Lottie arrived in Egypt, where she thought she might meet up with him. His father found out about his son’s death on 4 August. Lottie didn’t know until November, when her unopened letters to Leddie were returned to her, one of them stamped ‘KILLED RETURN TO SENDER’ (below)

Going home

At the end of November 1915, the Maheno carried invalided troops and a bereft Lottie back to New Zealand. After arriving home on 1 January 1916, Lottie worked again at Auckland Public Hospital and cared for her ailing father.

Her sweetheart ‘Sonnie’ was conscripted at the end of 1917 and, despite an appeal went into Featherston Military Training Camp six months later. Married by now, to Sonnie, Lottie had a final stint of military nursing at the camp’s hospital (below) during the 1918 ‘flu pandemic.

War’s end

After the war, Lottie supported her local Returned Soldiers’ Association (RSA). She was also involved with the Auckland Ex-servicewomen’s Association, which sold poppies for Anzac Day. Material related to her military nursing is held in the library at the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

Hello

I was interested in reading and seeing Lottie. I have done a thesis on Matron Eva Brooke, on 2 ships The Meheno and the Marama. Lottie was under the command of Matron Eva Brooke and she has an extraordinary story to. Eva was a quiet little lady with a big contribution during the war, in total 5 trips to Gallipoli.

Thankyou for sharing Lottie. Maybe you could do the same for Eva as her family are still alive and I have a close connection to them. My sister has raised Eva’s great niece’s and nephew.

Respectfully

Denise Wood QSM

I would like to know why they chose her and not one of the other 79 nurses?

Hi there

Thanks for your question. We chose Lottie for several reasons. Firstly, we decided to focus on a nurse who served on the Maheno hospital ship. This is because nursing on the ship was the closest that NZ nurses got to Gallipoli. The hospital ship also demonstrated a strong link back to the people who were in New Zealand. We didn’t have enough space in the exhibition for this important part of the war experience so we had to be clever, and used the hospital ship to stand in for people at home (who also they raised enormous amounts of money to equip the Maheno). That meant we had a long list of about 12-14 nurses to choose from. Our second criterion was that our Maheno nurse had to have written about her experiences in letters or in a diary for example. This was the case with Lottie, whose personal WWI nursing papers are at Auckland War Memorial Museum. WWI nurses papers are very thin on the ground compared to those of soldiers, so we were very lucky. It was just by coincidence that Lotties’s story, which involved the death of her brother Leddie on Gallipoli and the delay in her receiving news of this, was also very powerful and moving.

I hope that explains our decision making process.

Kind regards, Kirstie Ross, History Curator.

Hi – I am wondering why it took so long for Lottie to find out that her brother Leddra was dead. The Records Office in Egypt knew in late July and her father was told in early August but it seems that no one told Lottie. She would have missed this news when the Maheno arrived in Egypt and left for Gallipoli, but is it reasonable to believe that not one New Zealand officer put Lottie out of her misery while she asked people about her brother – and that her parents in New Zealand deliberately did not tell her over a period of three months? I wonder if you can shed any light on this?

Hi Jane

This is an interesting and important question – I too wondered how this could happen and why there was such a lag in the time in Lottie getting written news of her brother’s death.

I’ve reviewed the letters that Lottie wrote to her sweetheart Charles ‘Sonnie’ Gardner (later her husband) – these are held in the Auckland War Memorial Museum Library. None of the letters mention how or when she learnt of Leddie’s death, and they definitely don’t refer to her trying to obtain news from official military sources in Egypt.

In the letter Lottie wrote on 22 August 1915 to Sonnie, having been in Port Said, she noted that: ‘We hope to be at the Dardanelles now in few days [sic] and are all busy with our final work, se can’t find out much New Zealand news, so have not heard of Leddie at all yet. May hear more from Alexandria’.

A letter written later that day from Alexandria, again to Sonnie, refers to how hard it was to get any news: ‘We leave tomorrow for the Dardanelles, so just to say goodbye I sent you a cable today and was nearly asking for a reply but was afraid it would not come before we left. It’s most difficult to obtain any news here. Casualties are not reported – they say they are dreadful – to see the wounded well its awful!’ I would have expected her to mention the news of Leddie’s death had she learnt of it here even if through unofficial channels. And the tone of the letter does not suggest that the writer is stricken with grief

.

These letters reveal two things that contributed to Lottie’s lack of information. Besides the many weeks it took for mail to get from New Zealand to the Mediterranean, the Maheno was rarely in one place for an extended period of time. This meant that the mail was always arriving after the Maheno left a place or was waiting for it when it came back.

In a letter written in Malta on 13 September 1915 to Sonnie, Lottie notes ‘Well I suppose it will be another month before we get any letters….I have not been able so far to find any one who saw Leddie, I have met several who knew him, but they never hear what becomes of their chums.’

And on 23 September, [from Valetta in Malta] she picks up this theme – the lack of mail – again: ‘Tonight there was mild excitement we got a mail-bag with a few letters and papers; they say our mails have gone down in a transport, anyway they were letters written about time we left [ie 10 July 1915] – none from Home. I had one from you when you returned to Wellington just after I left, you ask in it if I would like papers. I hope that there are some on the way…. [which suggests she hadn’t received any] ‘One might say we haven’t had a mail yet at all. In future I believe our mail is to be sent from GPOW [Wellington] to Lemnos, so we will get it sooner.’

And on 8 October to Sonnie, [from Alexandria] ‘We hear last night our mail is in Malta, so it will follow us now and we will begin to get mails regularly’. However, the Maheno left for London that same day and did not get back to the Mediterranean until November, visiting Malta 6-7 November and then Mudros (on the island of Lemnos), 9-10 November.

I know that their brother Owen wrote to Lottie on 20 August 1915 from military camp NZ and mentioned Leddie’s death, which he heard about on 5 August, from their father (their mother had died some years earlier) who as Leddie’s next of kin would have received the official telegram announcing the death.

Owen’s letters are also in the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Leddie’s service file contains the official report of his death dated 2 August 1915 but it you may also want to check with military historians who will know the intricacies and formalities around who was notified about a soldier’s death – and when.

This letter would not have reached the Mediterranean until around the first week of October. As Lottie noted on 8 October, in Egypt, the mail destined for the Maheno was in Malta at the date, so it’s entirely possible that she didn’t get this until she was on Lemnos 9-10- November. I’ve pieced this together from timeline of the Maheno’s movements in Gavin McLean’s book The White Ships (2013) [NB error, 15-16 Aug Mudros should be 25-26 Aug] which makes clear how unlikely it would have been to get post in a timely fashion.

This is as much help as I can be – the documentary evidence, combined with Le Gallais family history strongly points to Lottie’s lack of knowledge from official sources and from home, of her brother’s death until near the end of her time nursing on the Maheno. I would estimate she received letters with the news she had been dreading in November 1915.

All the best

Kirstie Ross

Thanks for this Kirstie – I will be able to slip in some of this extra detail into the Gallipoli programme.