Despite their age Carleton Watkins’ photographs have an enduring appeal. Their large scale and simple beauty makes them stand out amongst the vast array of nineteenth century landscape photographs. Often Watkins’ photographs don’t simply document or show facts – they disorient our sense of identity and place in front of a scene. Sometimes finding perspective and scale in Watkins’ photographs is a matter of opening your mind.

Much has been written about Watkins and there is still more to come. American art critic Tyler Green is working on a new biography of the photographer. Green has also written a moving personal essay, Return to Round Top, about a photograph by Watkins taken in the Sierra Nevada mountain range that reminds him of a childhood trip his family took to the area. Green’s essay is a great example of the way historical photographs can create links between personal experience and memory and history.

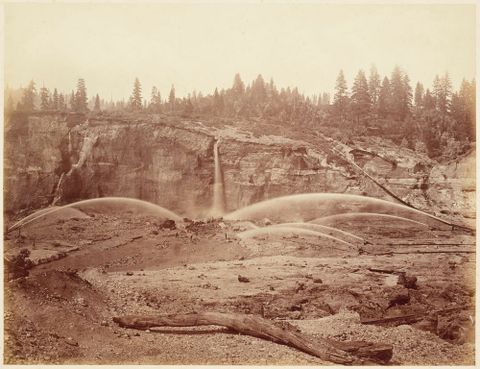

Watkins’ photograph of hydraulic mining operations: Malakoff Diggins, Nevada County, California, (above) is an image of sublime industry in action and had me thinking of one of my favourite essayists, celebrated American journalist, Joan Didion. In ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’, published in Time magazine in 1967, Didion chronicled the time she spent among the hippie community of Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco. She describes a plan of some of the men to go up to the Malakoff Diggins in the Nevada Valley, which Watkins made famous through his photography. The aim was to chill out and escape from the escalating tension (both personal and legal) and to ‘drop’ acid. There was talk in the hippie community at the time of forming a commune there. In this instance the trip doesn’t happen and Didion is disappointed to miss the potential of interpreting it and weaving it into her narrative.

Watkins’ photographs have many features that appeal to contemporary audiences. The size and scale of his negatives and prints, along with the subject matter, make a big impression. His epic photography expeditions to remote parts of California during the 1860s, involving teams of men and mules carrying camping provisions, large scale glass plates, along with a custom camera big enough to hold them, safely in and out remote parts of California during the 1860s still capture the imagination. And there is no doubting the appeal of looking at his prints in their original form as nineteenth century albumen contact prints – not enlarged and not reprinted with modern materials.

Watkins’ work is also inadvertently captivating – he didn’t set out make art and would never have anticipated the interest in and value of his work today (he died in poverty in an asylum). Watkins went to the Nevada Valley to take photographs of the Malakoff Diggins and other sites as commissions for mining companies that were removing precious metals for profit and reshaping the landscape as a result. His photographs were then exhibited at international exhibitions with the focus on showing the mineral deposits and area that they were found.

By the time of Didion’s interaction with the hippies, Malakoff Diggins was part of a state park. The people Didion met regarded it as a redemptive space, a place to clear the mind and refocus their vision of the world in a landscape itself reformed from its capitalist past into a sanctuary. Ironically the hippies never got there, but then they were always stronger in terms of idealistic vision than practical effectiveness.

But my point is this: whether we consider Watkins, Green, the Malakoff Diggins, Didion or the Haight-Ashbury hippies, the landscape of California, despite capitalist motives, has been made into an iconic and enduring symbol of personal vision, hope and loss.

Visit the exhibition ‘Carleton Watkins’ in the Artist on Focus gallery, level 5, Nga Toi / Arts Te Papa on now.

Read how photographer Wayne Barrar and poet Kerry Hines respond to this exhibition of historic landscape photographs by Carleton Watkins.

Lissa Mitchell – Curator Historical Photography

Follow Lissa on Twitter @rainyslip