There are times in the life of a curator when you see something you would really like to use in an exhibition or publication but have no immediate opportunities. Or you feel that your attraction to it is too personal, and other people wouldn’t feel the same way. So you tuck it away in your memory.

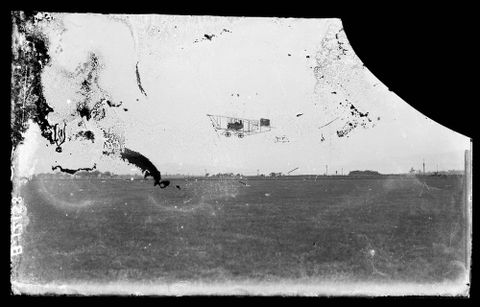

This was certainly the case with this image when I came across it while working in the former National Museum’s photographic darkroom in 1986. The glass negative was in very bad shape, with a large chunk broken off at the top right corner, and the image-containing emulsion flaking off in many places – probably due to damp at some point in its life. But, perhaps perversely for a museum professional, I felt these really added to the image of the aircraft in the sky. The fragility of the glass negative seemed to point to the achingly flimsy and vulnerable nature of the aircraft itself, distant and alone in the sky above empty paddocks. By extension, this fragility of both photographic record and aircraft also suggested the often brave and precarious nature of human aspirations. A companion negative showing the plane crash landed only reinforced this impression.

At the time I knew nothing beyond what was recorded in the negative catalogue – the date (1914), photographer (James Parry), that the pilot was called Scotland and he was flying at Otaki. In a way, I didn’t need to know more, because it was the emotional resonance that was important to me, not the historical facts. But when I selected it for my recent book New Zealand Photography Collected (Te Papa Press, 2015) and for the associated exhibition within Ngā Toi (to 7 August, Te Papa) I had to do some digging.

It turns out that the flight was the earliest in the Wellington region, though by no means the first in New Zealand: the earliest well-documented case of sustained and controlled powered flight was by Vivian Walsh in 1911 at Papakura. But the 22-year-old Scotland was the first to fly overland, from Invercargill to Gore in 1914, as part of a display tour up the country. The Otaki flight was part of this tour. Scotland was also the first to carry airmail, though the single parcel wasn’t postmarked and was delivered less than conventionally by dropping it to a friend as he flew over Temuka on the way north from Timaru.

The wonders of flight and its new technology cast a strong emotional spell at the time. A Dominion reporter at Otaki wrote, “It is a beautiful machine, a beautiful mechanical bird. …It is so light and strong, and (apparently) so perfectly constructed that one becomes almost fascinated by it and filled by a desire to try it. Get into the pilot’s seat and you feel so comfortable and secure that you have no wish to get out until you have flown. ‘Try the weight of her’ someone suggests, and you find the huge bird so light that Mr Scotland could almost carry it about with him.”

The light weight of Scotland’s French-made Caudron biplane may have been a liability though. On his first test flight at Otaki the plane tipped over after hitting a rut in the paddock and was damaged (though Scotland was unhurt). In the photograph above you can see spectators carrying the machine back with damage to the leading edge of the lower wing and undercarriage wheel clearly visible on enlargement.

Although Scotland later made a successful demonstration flight at Otaki on 29 January 1914, on a gusty March day in Wellington the aircraft was completely destroyed when he hit a downdraft and crashed into trees above Newtown Park. He suffered only a sprained wrist but was shaken and angry, feeling he had been pressured into flying by fee-paying spectators after successively postponing the demonstration flight for four days due to strong winds: “I cannot go anywhere in the city,” he said, “without meeting some man who considers that he knows more about flying than I do… Had it not been that I had such an antagonistic and unsympathetic crowd to deal with to-day, I should certainly not have tried a flight.”

Scotland imported a larger version of the Caudron in September, but had another mishap when an undercarriage wheel fell off on take-off and the aircraft flipped nose first. Scotland was catapulted out of his seat, again escaping serious injury, but the plane was a twisted and broken mess. It was repaired, but Scotland left New Zealand soon after to serve in the Royal Flying Corps during WWI.

“Sweet dreams and flying machines in pieces on the ground.”

– James Taylor, Fire and Rain, 1970

Athol McCredie

Curator of Photography

I have a couple of photos of Scotland’s later biplane, the Caudron photographed in Christchurch in 1914 on by website – here:

http://earlycanterbury.blogspot.co.nz/search?q=scotland%27s

This could be the later Caudron, the two seater, though he also flew his original single seater at Christchurch. The two-seater was seen in a display at the Christchurch Show in November 2014.

Thanks for a great picture and story Athol.

Did I see this image in the Air NZ exhibition at Te Papa?

You would have seen the photo in the link I added to the Kapiti Coast Council which has a photo of Scotland in front of his plane. That was in the Air New Zealand exhibition. It is in the collection of the Kapiti Aviation Society Inc.